(Lack of) Evidence for pandemic NPIs

A response to Dr. Tom Frieden's article in WSJ + Q&A about our new publication on pandemic RCTs

Dr. Tom Frieden’s new article in the WSJ made me consider how little good evidence we actually have the interventions he praised as lifesaving during the pandemic were effective. He draws a lot of conclusions from confounded observational data & early modeling studies. The reason I bring it up is it bothers me that many people will look back on the pandemic thinking we had good evidence masks, lockdowns, or as he says “closure of indoor activities”, etc “worked.” We didn’t have good evidence and we don’t. And that’s important because if there is not widespread acknowledgement of that, we will continue to make inappropriate decisions based on the same sort of weak data in the future.

But first I have to say, he got this right: “schools were closed when they could have remained open”

Thank you. I have been saying that since Spring of 2020. But whatever it is those kids are doing.. that picture (they call it the “zombie walk” in the caption) should go straight to the Museum of Pandemic Absurdities.

But how did he draw this conclusion for schools & not the other NPIs? Ss for the masks and selective closures decreasing excess mortality, he seems to have entirely forgotten about the country of Sweden, which only limited gatherings to under 50 people and had very brief secondary school closures and very limited mask wearing and one of the lowest excess mortality rates in Europe.

He mentions this modeling study from New York City, which concluded all of the below measures “worked’ to some degree, but they have no comparison within the city to areas that did not close schools, issue stay-at-home orders, advise or mandate masks. They actually could have randomized different areas to different interventions.

And, no that would not have been unethical, especially knowing now better evidence has suggested closing schools and mandating masks did not work. What may have been happening here was we were seeing this was a seasonal respiratory virus or cases may have just been decreasing on their own.

Europe’s cases also decreased that Spring but Sweden’s death rate from covid-19 declined more slowly- the question is why. What was it about their response that led to this? Something with nursing homes? We are left wondering.

And one thing that interests me about a study from Europe he cites as evidence lockdowns worked is the lack of dose response to the interventions. “First”, which I understand is “early”, did not have more impact than later enactment of the below interventions.

And, in the end, looking at pandemic age-standardized excess mortality, Sweden may have not done as well in the first mile of the race but did not lose the marathon when comparing it to other European countries or even its Nordic neighbors. By Paul C. I don’t like to make predictions, but it seems unlikely they’ll lose the ultramarathon either. Health was never just about one disease.

And what about the vaccination data he cites for effectiveness against death from COVID-19?

The data are confounded by better underlying health (at least 3-4x less likely to die from non-covid causes) in the more highly vaccinated in the US and skewed by the fact people with unknown vaccination status are considered “unvaccinated” and are more likely to be uninsured/lower SES etc. So is 10x less likely correct? The answer is- probably not given healthy vaccinee bias. We must be honest, that without any randomized data - or even falsification endpoints on the bivalent boosters, we are currently flying blind in terms of estimating their effectiveness against severe disease and death from COVID-19. All of the data we have are observational and when they are not reported with non-covid death or hospitalization rates by vaccination status need to be assumed to be confounded by healthy vaccinee bias until proven otherwise.

Then he presents evidence he believes shows masks “worked”

But what he cites are many confounded observational studies. He fails to cite any RCTs except Bangladesh, the results of which have been found to be too uncertain due to sampling bias to be considered significant; there are issues beyond sampling bias as well. He also fails to cite the best peer reviewed study we really can get causal inference from - the regression discontinuity study from Spain, which found no effect of mask mandates on infection or transmission. He also does not cite all of the pre-pandemic randomized studies for influenza/influenza like illness that were negative!

But the above quote is what really got me. He says: “randomized controlled trials aren’t usually the best way to evaluate communitywide interventions, particularly during a pandemic.”

Okay- admittedly, that might be the case if you had good evidence of effectiveness- and particularly that the benefits outweigh the harms. But that’s simply not what we have or had for all of the pandemic NPIs. None of them. A very important part of public health is stating what we don’t know - and could have learned- but didn’t. And the mere fact we did randomized studies of NPIs during the pandemic shows we can do them.

—-Which bring me to the topic of a new peer-reviewed article I wrote with Vinay Prasad. It’s entitled “An evidence double standard for pharmacological versus non-pharmacological interventions: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic” and poses the (I thought) straight-forward question of why we require randomized trials of pharmacological treatments but, when it came to non-pharmacological interventions during the pandemic (school closures, lockdowns, mask mandates), they were not only recommended but required- often long term- without good evidence they worked.

Where did this assumption come from that COVID-19 NPIs would obviously work so well that their effectiveness would outweigh any harms? From wishful thinking? Is that what led many to accept studies of two hair stylists and phone surveys as good evidence?

When you consider how medical evidence typically works, it is generally assumed putting a pill in your mouth might not have the intended effect and can have side effects, so the efficacy and harms must be established before use is recommended. Why was it not assumed that interventions like school and business closures would also come with harms? Hubris? Unwillingness to acknowledge most things we think will work - and are even very plausible - don’t?

As we said, and Dr. Michael Absoud highlighted, NPIs can have wide societal consequences, which we undoubtedly saw with school closures and lockdowns, and should not be assumed to be of less consequence than side effects from medications.

As we mention in the article, Atle Fretheim and colleagues in Norway called for RCTs of school closures. However, Norway’s school closures were so brief - only 6 weeks; this may be why no randomized studies were undertaken. Because most of Europe reopened school in the spring and summer with observational data failing to note a surge in the community, schools there, for the most part, remained open.

But the US and much of the world outside of Europe had prolonged school closures and, honestly, the return to brief school closures time and again across Europe (though not in Sweden) with the emergence of new variants was never evidence-based. With data from Germany and Brazil showing no correlation between school closures and COVID-19 cases or mortality (the latter studied in Brazil), it has only become clearer with time the harms of school closures vastly outweighed any undetected benefits. And this is an example of what can happen when humans make evidenceless assumptions and force people to comply. This is why we should require robust evidence of effectiveness of NPIs (just as we do for pharmacological interventions) before they are recommended, let alone mandated.

While most astute readers seemed to understand the argument our paper made, some of the comments to my post on Twitter surprised me, but maybe maybe others have similar questions.

Take this comment:

My favorite question is “can cups hold water?” TheyCallMeTarz is describing things we can observe the nature and effectiveness of directly with our senses (in this case mostly just with our eyes). I think essentially everyone would agree we don’t need an RCT when we can just use our eyes.

Also, I greatly prefer water without ice. But that’s sort of beside the point.

It’s the same for parachutes and not jumping in front of a moving bus. You can see immediately these things work. You don’t need a randomized study to tell you . This is simply not true for masks or closures or CO2 monitors because, even if mechanistically they “work”, humans are gonna human (a modification on Zeb’s virus gonna virus, of course).

And we have a lot of observational data that places with mask mandates and school closures did not do any better at curbing COVID-19 spread than those that didn’t. And there was and is significant debate about whether or not they would work (equipoise), so RCTs were indicated if they were to be implemented.

But this gets to another critical part of our article: who needs to generate the evidence to justify recommending or imposing an intervention? Of course it is the people who are recommending or requiring it.

And this is the point Dr. Lam (below) may be missing. It is public health officials who need the data to justify their recommendations. It is not up to the people who are not pushing the recommendations to do the studies.

There is a very long list (infinite, I suppose) of things I don’t recommend and also don’t do RCTs of. I do however commend the researchers who have done RCTs of NPIs. I was surprised when writing our article to see the RCT of CO2 monitors for maintaining CO2 below a certain level in hospital rooms… the RCT was negative; the intervention did not work because the CO2 levels were no different in the rooms with the monitors (and instructions given to keep below a certain level) and those without. The authors state one of the reasons was patients got too cold with the windows open.

But more to Dr. Lam’s point, of course RCTs for mask mandates have been designed and run and were deemed ethical by IRBs. Just look at the two Cochrane reviews of randomized studies for masks. And I was recently in a discussion on Twitter about the opportunity of studying masks in the healthcare setting as hospitals drop mask mandates… and I said “yes, good idea!” This would indeed be a good time and opportunity to do an RCT! So, it’s not like these studies haven’t been or can’t be done. As long as there is equipoise they are ethical and should be considered necessary when existing observational data are insufficient and public health officials wish to recommend the intervention for widespread use.

But here we are, 3 years later and we never generated high quality evidence the NPIs that were recommended (and even forced) worked.

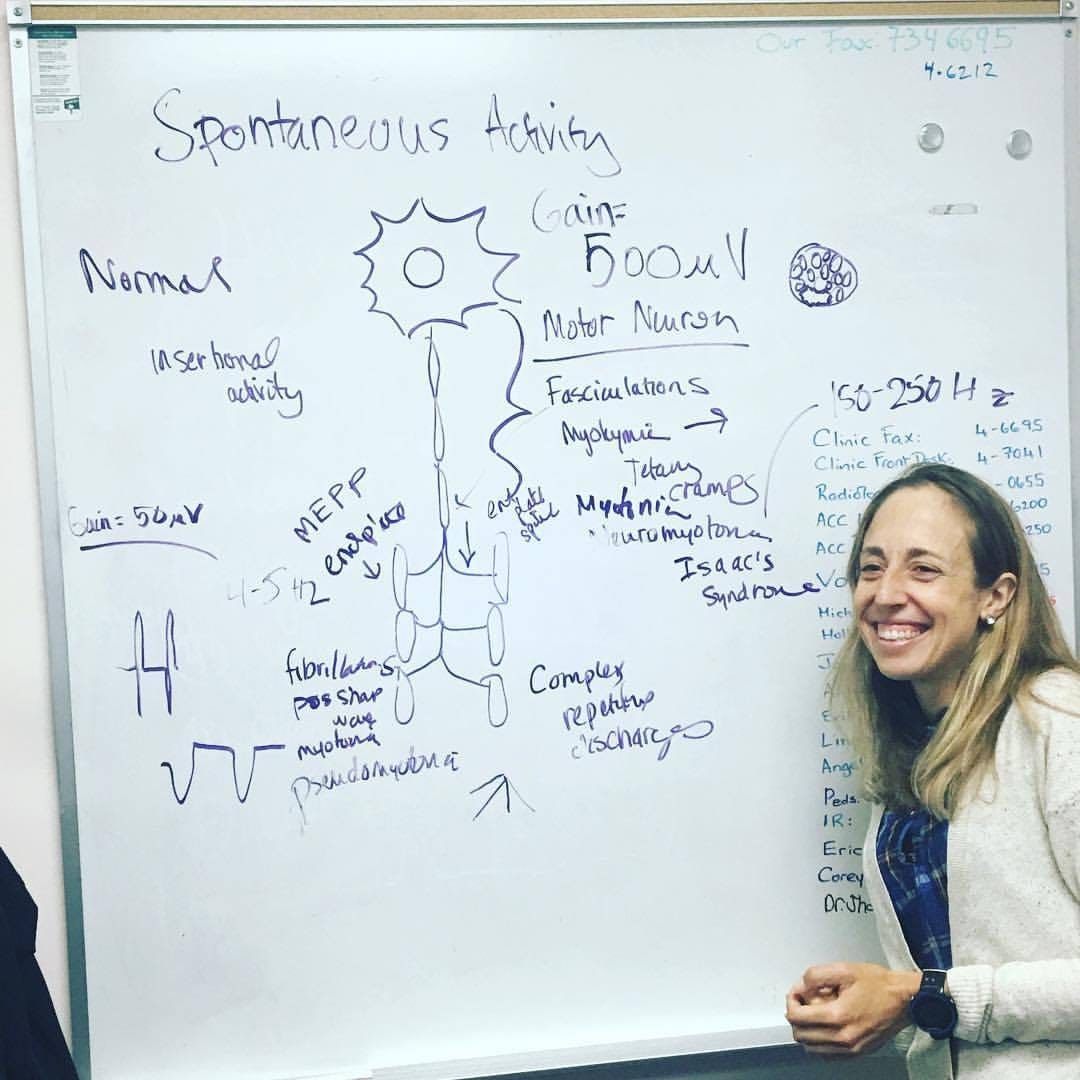

On a different note, congrats to all the senior med students who just matched! Crazy to think I went through the match twice matching into ophthalmology and then PM&R - both great for nerding out. If you are doing residency in PM&R you are in for such a treat because we see such a wide range of diseases and problems and really get to know our patients well. Delightful. Just ran across this photo from 5 years ago during residency at UC Davis lecturing on one of my favorite topics- EMG spontaneous activity

Be happy, my friends. Do what you love and stand up for what you believe is important; sometimes that might mean generating the evidence for or saying we don’t know how well society-wide interventions work- and that harms may outweigh the benefits; there are many ways for us physicians to speak up on behalf of our patients.

Okay, before I end, what did I get wrong? I appreciate being corrected.